1951

After the Second World War, Finland did not participate in the Triennale di Milano until IX Triennale in 1951. Initially, Finland did not intend to participate at all due to lack of funding.

In 1950, Tapio Wirkkala presented the exhibition idea to H. O. Gummerus, Wärtsilä-Arabia’s PR Manager, and asked the company for financial support. Gummerus was immediately enthusiastic about the idea and recognised the opportunity to take Finnish design to the world. He negotiated the funding for the Finnish exhibition jointly from the state and private businesses such as Wärtsilä-Arabia, Iittala, Boman and Artek.

Gummerus was sent to the Triennale as a representative of the Finnish state. With his language skills, he took the role of helper and liaison to the Triennale organisation for not only Finland but also other participating countries. H. O. Gummerus was a journalist by education and had lived in Rome in his childhood and youth, as his father Herman Gummerus had served as Finland’s Envoy to Rome.

Later, he had studied in Paris and New York. In October 1952, he became the first Director of the Finnish Society of Crafts and Design, and from there began his work as a promoter of Finnish design, lasting almost a quarter of a century.

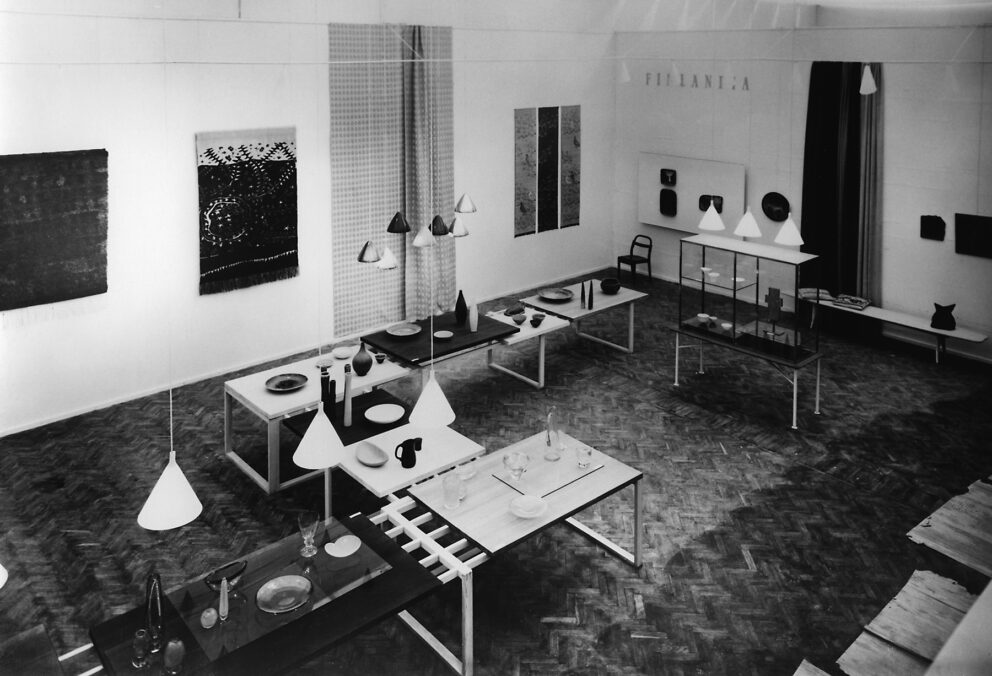

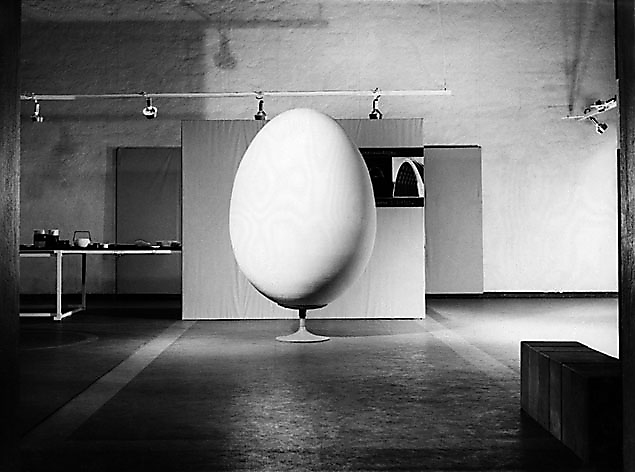

The IX Triennale di Milano in 1951 was an international breakthrough and a great victory for the Finnish applied arts. The Finns received a total of 25 awards, six of which were the highest prizes, the Grand Prix. Tapio Wirkkala was the exhibition commissioner and exhibition architect and won three Grand Prix, one of which was for exhibition architecture.

The Finnish section was simplified and elegant. According to Wirkkala, austerity and minimalism were stylistic means for disguising the shortage and deprivation that prevailed in post-war Finland. There was an abundance of glass and ceramics on display in the exhibition, but only a few textiles, for example.

Foreign magazine reviews praised the objects’ stripped-down design language and restrained colour scheme, and the objects were found to reflect Finnish nature. The Italian magazine Domus dedicated 14 pages with pictures for the Finnish section. The success gave rise to talk of “the miracle of Milan”.

Photo: Pietinen